A landmark piece of legislation passed in 1823 was fundamental in the story of Scotch whisky’s global success and saw a slew of distilleries gaining their official licenses to distil the following year. Tom Bruce-Gardyne reflects on the Excise Act and the bicentenary celebrations of a number of distilleries founded in its wake.

For the whisky writer Dave Broom, the importance of what happened just over 200 years ago cannot be overstated. “What the 1823 Excise Act did,” he says, emphatically, “was a fundamental redrawing of what whisky is, and what whisky would become. It was the most important Act ever in Scotch whisky, that created Scotch whisky as we know it.”

For fellow amateur whisky historian, Arthur Motley: “It was a brilliant piece of legislation.” Now MD of the Dormant Distillery company, owners of Royal Mile Whisky, Arthur had always swallowed the line of countless whisky books that the Excise Act was purely a matter of tax. That by lowering the amount to £10, illicit distillers simply took out a license and came in from the cold.

But there was way more to it than that, as he discovered in a deep dive into its 51 pages, swimming through the reeds of its 19th century legalese.

“Have you read the Excise Act?” Arthur asks, when we meet. To my eternal shame I admit it’s still on my to-do list, but his enthusiasm makes it sound – almost tempting. “It’s basically a blueprint for building a distillery,” he explains. “It is so proscriptive, saying you have to have not only this size of still, but you have to have these pipes, these locks and all sorts of different equipment.” In other words, the man making moonshine in Sir Edwin Landseer’s Illicit Highland Whisky Still, painted in 1829 and beloved by Victorians, would have had no chance.

the Excise Act a read

He might have found the £10 for a licence but not the £300 or so, almost £30,000 in today’s money, needed to turn his primitive hovel into something that would satisfy the strictures of the Excise Act. His only chance of making legal whisky after 1823 would have been as a stillman employed by someone with the means to build a proper distillery.

Shaping whisky’s taste

The Act’s intent was obvious – it was about maximising revenue for the Treasury and repairing the leaks in the system, as well as stamping out lawlessness for the sake of public morals. Yet it did wonders for the drink. “It wasn’t preordained that Scotland would become a successful whisky-making nation,” says Arthur about an industry whose exports were worth a staggering £5.6 billion last year. “Unless people could invest capital, and employ others to go down to London and travel overseas, it would never have happened without the security of a legal framework.”

And while there is no mention of ‘flavour’ anywhere in those 51 pages, it did help shape the taste of malt whisky. Its rules on measuring and recording every detail of production improved consistency, while allowing spirit to be stored under bond meant that distillers were no longer penalised by the taxman if they wanted to mature their spirit. One imagines they and their customers soon began to appreciate the mellowing effects of age.

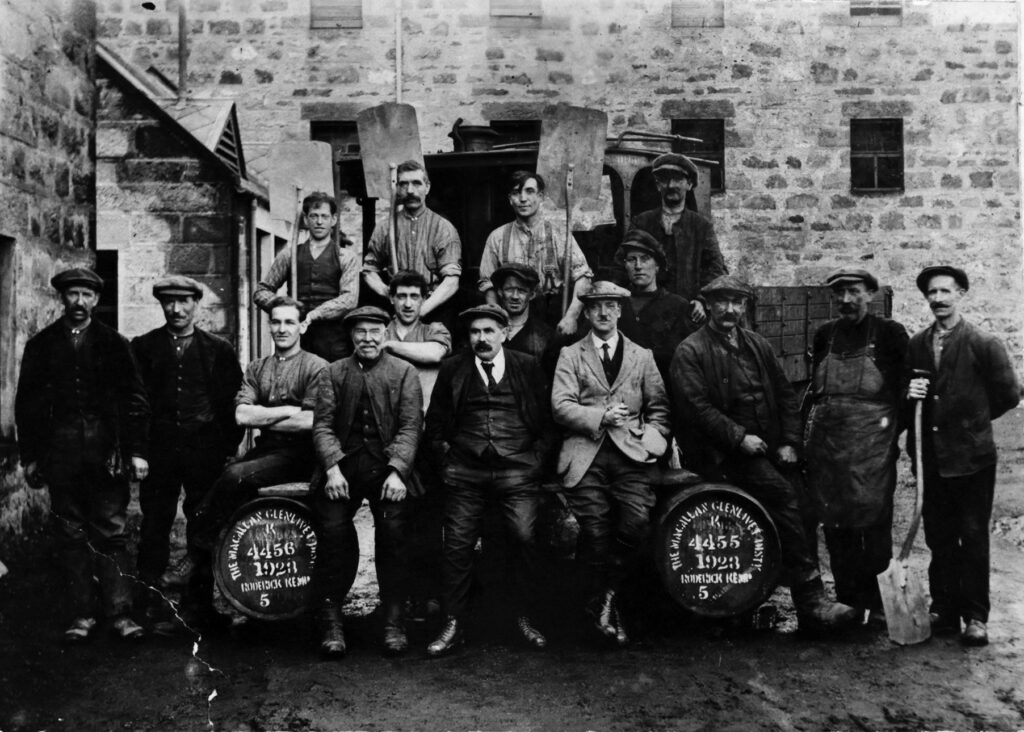

Because of all the requirements in equipment and the need to employ scores of builders and coppersmiths it delayed the founding of some of the most famous distilleries in Scotland to 1824. As a result, this great bicentenary is being celebrated individually by the likes of The Macallan, The Glenlivet, Cardhu and Fettercairn.

WHISKY FIT FOR A ROYAL VISIT

The Glenlivet was licensed to George Smith on 9 November 1824, but before then “we know he was making it,” says Robert Athol, the Chivas Bros archivist. He accepts that ‘Glenlivet’ was a generic term for what was made in a glen that was bristling with illicit stills, but says: “My hunch is that it was George Smith’s Glenlivet that was being consumed in the most part.”

Was his the whisky that George IV famously demanded in 1822 in Edinburgh on the first royal visit to Scotland for almost two centuries? Robert would like to think so, given that Smith’s landlord, the Duke of Gordon, would have been at court and may have slipped the king an illicit dram of his tenant’s whisky prior to his visit. It’s a nice story, but Arthur Motley reckons it was more likely Sir Walter Scott who whispered the ‘G’ word in his ear when he landed in Leith.

The event, stage-managed by Sir Walter, at times resembled a pantomime, with George IV playing the part of the pantomime dame. At one of the main receptions, his portly frame was swathed in tartan, his face slicked with rouge and powder, and there was a Glengarry bonnet with eagle feathers perched on his head. Instructed in what to wear, he was no doubt also told what to drink. Soon after, comes the first ever mention of ‘Glenlivet whiskey’ in Australia in the Sydney Gazette on 11 March, 1824. One imagines it was generic Glenlivet, but who knows?

Double century celebrations

Nine months before Smith took out a license, the Scottish Excise Board minutes from 23 February 1824 mention the distillery at Fettercairn ‘about to commence’. Sir Alexander Ramsay, the local laird and MP, had seen the Act through parliament and approached James Stewart, one of his tenant farmers, about the opportunity, presumably because he knew Stewart had run a still on the side. Fettercairn was soon in production, and with an experienced distiller and a wealthy landlord, the venture prospered after some tricky years competing with all the illicit whisky still being made.

The distillery is celebrating its big birthday with its staff and their families and the local community, and “with something top secret and truly special later in the year,” says Fettercairn’s global brand controller, Thom Watt. “We can’t say too much about that just now, but if you’ve been waiting 200 years for it, what’s a few months more?”

The Glenlivet has released a raft of special editions and is running a series of ‘experiences’ at the distillery, including ‘The Visionary’, where guests will get a glimpse of the latest still house ‘unseen by the public eye until now’, it is claimed. The Macallan’s celebrations include a nightly performance by the Cirque du Soleil at the distillery throughout May ‘offering breathtaking performances, intriguing stagecraft and signature tasting experiences’, to quote the press release.

But whatever the various distilleries get up to, 2024 is a belated bicentenary for the entire industry. The Excise Act was a last chance to establish the business of Scotch malt whisky after so many botched attempts. Had it failed, we’d probably all be drinking something Irish.